Hannah (1999)

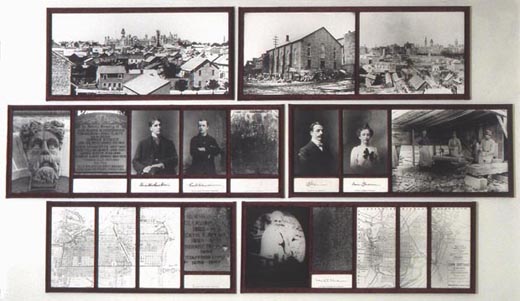

Installation Views: Ottawa Art Gallery/Galerie d’art d’Ottawa, 2000-2001. Photos: Tim Wickens.

General Description

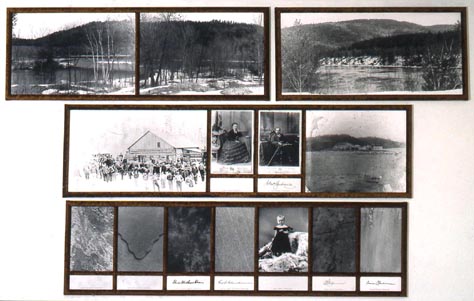

An installation fits a modest sized room comprised of five parts: Hannah [title piece], Bytown, Pembroke, des Joachims, Ottawa plus a small addition, Citations. These include twenty-one multi-sectioned velour⁄wood⁄plexiglas frames containing archival silver prints; five wood and velour covered plywood shelves displaying various objects, texts and newspaper notices; and a framed silverprint, the Citations.

The largest overall dimensions for an individual section are found with Ottawa: 2 meters X 2.69 meters X34 centimeters. Collection of the Artist.

Release

Lee Dickson: Hannah, 7 December 2000 – 4 February 2001, Curator: Sylvie Fortin.

The Ottawa Art Gallery is pleased to present Hannah, a new historically-informed installation combining objects, texts and images by artist Lee Dickson. Hannah pieces together the life of the artist’s great-great-grandmother, Hannah Burns, who was born in Bytown in 1835 and spent her entire life in the Ottawa Valley. The details of her life can be sketched through those of men – her father, brothers, husband and sons – whose lives were better documented. The absence of specific information about this woman’s life, character, thoughts and emotions as well as the necessary recourse to official documents and the recorded histories and stories of others shape a factually-grounded outline, the data-proficient screen of an existence that the artist reinvests with materiality and tactility. Combining this document-founded story and the seductiveness of physical materials, the artist creates an environment open to reconfiguration, shaped by our desires and fantasies...An Artists with Their Work Program, which is organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Media Release, 24 November 2000, The Ottawa Art Gallery.

Lee Dickson: Hannah, 7 décembre 2000 – 4 février 2001, Commissaire: Sylvie Fortin. La Galerie d’art d’Ottawa présente Hannah, une installation inédite d’inspiration historique de l’artiste Lee Dickson. Hannah conjugue objects, texts et images, et reconstitue la vie de Hannah Burns, l’arrière-arrière -grand-mère de l’artiste. Née à Bytown en 1935, Hannah Burns passe toute sa vie dans la vallée de l’Outaouais. L’histoire mieux préservée des hommes de sa vie – père, frères, mari et fils – a permis d’esquisser son existence. L’impossibilité de retracer directement l’histoire, le caractère, les pensées et les émotions de cette femme, ainsi que le recours obligé à des documents officiels et aux récits de vie d’autres personnes, donne un profil factuel, l’écran savant d’une existence que l’artiste ravive par la matérialité et le toucher. Grâce à ce récit documenté et à l’attrait des matériaux, l’artiste propose un environnement ouvert aux configurations nouvelles, une expérience que façonnent également nos désirs et fantaisies.

Communiqué, 24 novembre 2000, La Galerie d’art d’Ottawa.

The Texts and Details

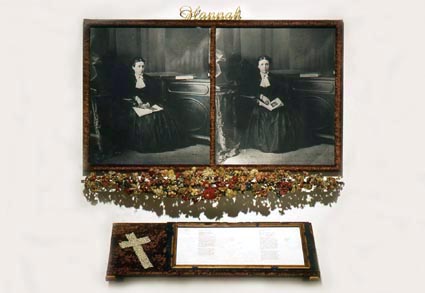

HANNAH [1835-1915]

Installation view, Ottawa Art Gallery/Galerie d’art d’Ottawa. Photo: Tim Wickens, 2000-2001.

Hannah was my great-grandmother. The family history reveals little of her life. A Norman portrait of her sitting quietly, perhaps painfully still for the camera, reveals a pensive expression. Her name was Hannah Burns. She married a young Irish doctor, John Deaker Clendinnen. These details are all that survive about her from the family lore passed on to the few of us who are descended from her. The best I can do is to situate her in the lives of the men who were a part of her life: her father, brothers, husband and sons. I have found that fragments of their histories are better recorded in local repositories.

Hannah was very religious, this I know. Her obituary describes her as having had "a long and beautiful life." She lived to be eighty years old. What she did with her days, I do not know. She was not, it appears, an important person beyond being a daughter, wife and mother. If she wrote poetry, wove exquisite lace, inspired others, I can't say.

Hannah était mon arrière arrière-grand-mère. L'histoire familiale révèle peu de choses sur sa vie. Un portrait delle pris par Norman, oû elle se tient discrètement assise, peut-être mal à l'aise de devoir restée immobile, la montre pensive. Elle s'appelait Hannah Burns. Elle avait épousé John Deaker Clendinnen, un jeune médecin irlandais. Ce sont les seuls détails à son sujet qui subsistent dans la tradition familiale et qui ont été légués aux quelques descendants que nous sommes. Le mieux que je puisse faire, c'est de la situer dans la vie des hommes qui ont fait partie de sa vie : son père, ses frères, son mari et ses fils. J'ai constaté que ce sont les archives locales qui ont le mieux préservé les fragments de leurs histoires.

Hannah était très croyante, ça je le sais. Sa notice nécrologique la décrit comme ayant eu «une vie longue et belle». Elle a vécu jusqu'à quatre-vingts ans. Ce qu'elle faisait de ses journées, je ne le sais pas. Elle n'était pas, semble-t-il, une personne importante, à part le fait d'être fille, épouse et mère. Si elle a écrit de la poésie, fait de la dentelle exquise ou inspiré son entourage, je ne saurais le dire.

BYTOWN [1835-1857]

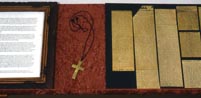

Photos: Studio details by the Artist and installation views, Ottawa Art Gallery/Galerie d’art d’Ottawa, by Tim Wickens, 1999-2001.

Hannah was born in Bytown in 1835. She was the third daughter of an Irish cobbler, John Burns, and his wife, Amelia Astleford. John and Amelia came from Wicklow County, Ireland. They were amongst the impoverished Irish that Colonel By encouraged to settle in the Canadian Frontier. They arrived in Bytown in 1827, a year after the Colonel started work on the Rideau Canal. In these early days, the brawling frontier settlement of Bytown was reputed to be the toughest town in Canada.

There were at least seven children in the Burns or Byrne Family. They appear to have lived in a small one and a half story frame house in the Market area around Wellington Square known as the Upper Town Market. Possibly, a simple rocking chair was the only furniture brought from the Old Country. This treasure survives and is the only family heirloom handed down through Hannah's brother William's family.

Sometime after Hannah married, her father became the first tax collector or messenger as it was called in those days. He managed to buy three small lots at the corner of Slater and Bank Streets. This then, remained the Burns home for some years to come.

Hannah est née à Bytown en 1835. Elle était la troisième fille d'un cordonnier irlandais. John Burns, et de sa femme, Amelia Astleford. John et Amelia venaient du comté de Wicklow en Irlande. Ils faisaient partie de ces Irlandais appauvris que le Colonel By avait encouragés à venir s'établir au Canada. Ils sont arrivés à Bytown en 1827, une année aprés le début des travaux entrepris par le Colonel sur le Canal Rideau. Dan ces premières années, ce village de bagarreurs, établi à la limite de la civilisation, avait la réputation d'être l'endroit le plus dur au Canada.

La famille Burns, ou Byrne, comptait au moins sept enfants. Il semble qu'ils aient vécu dans une petite maison à charpente de bois d'un étage et demi dans le secteur du marché, près du square Wellington connu sous le nom de Upper Town Market. Une chaise berçante est problement le seul meuble qu'ils aient emporté des vieux pays. Ce trésor a survécu et demeure le seul héritage familial à avoir été transmis par la famille de William, le frère d'Hannah.

Quelque temps après le mariage d'Hannah, son père devint le premier percepteur d'impôts ou messager, comme on disait dans ce temps-là. Il parvint à acheter trois petits lots de terrain au coin des rues Slater et Bank. Ceci allait devenir le foyer des Burns pour les années à venir.

PEMBROKE [1857-1869]

Photos: Studio details by the Artist and installation details, Ottawa Art Gallery/Galerie d’art d’Ottawa, by Tim Wickens, 1999-2001.

Hannah's oldest sister, Susannah, married Abraham Astleford in 1854. They moved up the Ottawa River to Pembroke, known as Campbelltown in those days. Abraham was an early merchant of this village, a town councillor and tavern inspector. Through them, it is likely that Hannah met the young Dr. John Clendinnen, the District Coroner of Pembroke Township and a local doctor⁄surgeon of Pembroke Town and vicinity.

Hannah and John married at the Metcalfe Street Wesleyan Methodist Church in Bytown in 1857. This church was presumably the Church Hannah and her family belonged to, as they were staunch Wesleyan Methodists. Hannah and John moved to Pembroke. Though Dr. John was an Anglican and their children christened in the Anglican Church, Hannah seems to have remained a Wesleyan Methodist.

The next year, at age twenty-three, Hannah gave birth to her first child, Lydia Charlotte. Over the course of the next fifteen years, she and John were to have six more children. They lived in a traditional one and a half story log home on a one and a half acre lot south of Pembroke Street. An elderly widow, Janet Cannon, lived with them. Lydia Charlotte died in 1867 at the age of nine, in Ottawa, at the Burns home.

Hannah's sister Elizabeth and brother Samuel also lived in Pembroke for a while. Samuel worked as a clerk, but by 1864, Samuel had returned to Ottawa. Of Elizabeth not much is known, it appears she never married. The elder sister, Susannah, was widowed around 1863. She was left with two small children and a Chancery hearing. She lost her husband's properties in Pembroke and was awarded a compensation of $300. Five years later, she married a widower, Thomas Baron Ellis, a prominent lumber merchant in the Ottawa Valley. They had a multitude of children between them.

Hannah's husband, Dr. John Deader Clendinnen, was the son of an eminent Dublin physician. Described as "very popular as a man and successful as a practitioner," John was also regarded as a somewhat eccentric personality. Most certainly an asset to the small lumber boom town of Pembroke, he worked, apart from his medical practice and coroner's profession, as town auditor. Although many issues of the local paper The Pembroke Observer do not survive, it is evident that Dr. John had a penchant for writing letters to the Editor. He was obsessed with mysterious deaths. An advocate of the poor, Dr. John travelled up and down the Ottawa River and around the local vicinity; caring for the sick and visiting lumber camps and shanties as doctors did in those days.

Dr. John developed a condition of Delirium Tremens destroying all hope of occupying an influential and honourable position in the small local society. He lost his practice and was forced to leave town.

La sœur aînée d'Hannah. Susannah, a épousé Abraham Astleford en 1854. Ils on déménagé plus haut sur la rivière des Outaouais à Pembroke, qu'on appelait Campbelltown dans ce temps-là. Abraham a été l'un des premier marchands de ce village, un conseiller municipal et aussi un inspecteur de taverne. Il est probable que ce soit par eux qu'Hannah ait rencontré le jeune docteur John Clendinnen, coroner régional du comté de Pembroke et médecin⁄chirurgien local du village de Pembroke et des environs.

Hannah et John se sont mariés à l'église méthodiste wesleyenne de la rue Metcalfe à Bytown en 1857. Cette église était problement celle à laquelle Hannah et sa famille appartenaient aussi, puisqu'ils étaient de fervents méthodistes wesleyens. Hannah et John déménagèrent à Pembroke. Bien que le docteur John fut anglican et que leurs enfants furent baptisés à l'église anglicane, Hannah semble être demeurée méthodiste wesleyenne.

L'année suivante, à l'âge de vingt-trois ans, Hannah donna naissance à son premier enfant, Lydia Charlotte. Au cours des quinze prochaines années, elle et John auront six autres enfants. Ils vivaient dans une maison en rondins traditionnelle d'un étage et demi, sur un lot d'un arpent et demi situé au sud de la rue Pembroke. Une veuve assez âgée, Janet Cannon, vivant avec eux. Lydia Charlotte est morte en 1867 à l'âge de neuf ans, à Ottawa, dans le foyer des Burns.

Elizabeth, la sœur d'Hannah, et Samuel, son frère, ont aussi vécu à Pembroke pendant un certain temps. Samuel travaillait comme commis, mais dès 1864, il était retourné à Ottawa. Je ne peux pas vous dire grand chose au sujet d'Elizabeth, mais je pense qu'elle ne s'est jamais mariée. La sœur aînée, Susannah, est devenue venue vers 1863. Elle se retrouva seule avec deux enfants et une audience dans la cour de la chancellerie. Elle perdit les propriétés que son mari avait à Pembroke et reçut une compensation de 300 $. Cinq années plus tard, elle épousa un veuf, Thomas Baron Ellis, un marchand de bois de charpente bien en vue dans la vallée des Outaouais. Ensemble, ils eurent une multitude d'enfants.

Le mari d'Hannah, le docteur John Clendinnen, était le fils d'un éminent physicien de Dublin. Décrit comme étant «un homme très populaire et un médecin prospère», John était aussi considéré comme étant quelque peu excentrique. Fort certainement un atout cette petite ville où l'industrie du bois était en plien développement, it travaillait comme vérificateur municipal en plus d'exercer sa pratique médicale et sa profession de coroner. Même si plusieurs numéros du journal local, The Pembroke Observer, n'ont pas survécu, il est évident que le docteur John avait un penchant pour l'envoi de lettres à l'editeur. Il avait une obsession pour les morts mystérieuses. Défenseur des pauvres, le docteur John se déplaçait tout le long de la rivière des Outaouais et dans les environs de la région, prenant soin des malades et visitant les camps et les cabanes de bûcherons, comme les médecins le faisaient dans ce temps-là.

Le docteur commença à souffrir du delirium tremens, et tous ses espoirs d'occuper une position influente et respectable au sein de cette petite société locale furent ainsi détruits. Il perdit son cabinet et fut forcé de quitter la ville.

DES JOACHIMS [1869-circ.1877]

Photos: Studio details by the Artist and installation details, Ottawa Art Gallery/Galerie d’art d’Ottawa, by Tim Wickens, 1999-2001.

The Clendinnen family moved up the river to des Joachims or "Da Swisha" as it is locally called, a small village on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River.

An old Mission and Hudson's Bay Post, des Joachims was gradually losing its small population. It was the last stop the Pontiac and later steamboats took up the river. The rapids at des Joachims, the most dangerous ones on the Ottawa, have a drop of twenty-three feet with an eddy and a whirlpool at the foot. A portage of three miles had to be made here to reach the upper waters of the Mattawa. After the railway extension was built through Pembroke in 1876, this traffic was diverted. The channels and businesses at this village dwindled to almost nothing. Mail arrived only three times a week and tourists with less frequency. Mr. Ingram, the school teacher, closed the school house in May of 1878 and left for Ottawa. By August of 1880 des Joachims boasted of nothing but two hotels, a store, telegraph office and one or two log houses. A third hotel, the best building in the place was converted into a church or meeting house.

Hannah's two youngest children were born at des Joachims. Possibly, her older children resided in Ottawa with her parents. It might be presumed that further education and training would be the reason, or possibly saving the children from the Dr.'s deteriorating condition.

In April of 1877, Dr. John, in a state of Delirium Tremens, slit his throat. He died almost instantaneously, in front of his family.

La famille Clendinnen déménagea en amount de la rivière, à des Joachims ou «Da Swisha» comme on dit là-bas, un petit village du côté québécois de la rivière des Outaouais.

Ancienne mission et ancien poste de las Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson, des Joachims se vidait peu à peu de sa population. C'était le dernier arrêt sur la rivière pour le Pontiac et pour les autres bateaux à vapeur qui suivirent. Les rapides à des Joachims, les plus dangereuses de la rivière des Outaouais, ont une chute de plus de sept mètres avec, au bas, un tourbillon et un remous. Il fallait faire un portage de presque cinq kilomètres pour atteindre les eaux supérieures de la rivière Mattawa. Une fois complétée l'extension de la voie de chemin de fer à travers Pembroke en 1876, la circulation fut déviée. Les chenaux et les affaires diminuèrent peu à peu jusqu'à presque rien. La poste ne venait que trois fois par semaine, et on voyait de moins en moins de touristes. Monsieur Ingram, l'instituteur, ferma l'école en mai 1878 et partait pour Ottawa. Dès mois d'août 1880, des Joachims ne pouvait se vanter que d'avoir deux hôtels, un magasin, un bureau de télégraphe et une ou deux maisons en rondins. Un troisième hôtel, la meilleure construction de l'endroit, fut converti en église ou lieu de runion.

Les deux cadets d'Hannah ont vu le jour à des Joachims. Ses enfants plus âgés habitaient peut-être avec ses parents à Ottawa. On peut présumer qu'ils étaient là pour parfaire leur éducation et leur formation, ou peut-être pour qu'ils soient préservés de l'état du docteur John qui se détériorait.

En avril 1877, le docteur John, en état de delirium tremens, se trancha la gorge. Il est mort presque sur le champ, devant sa famille.

OTTAWA [circ.1877-1915]

Photos: Studio details by the Artist and installation details, Ottawa Art Gallery/Galerie d’art d’Ottawa, by Tim Wickens, 1999-2001.

Hannah, with her children, returned to her parent's home in Ottawa. Two years later her parents, John and Amelia, died within less than three months of each other. John's mortgaged properties with two buildings were left to his sons, Samuel and William. Samuel was an accountant with a wife and small child. William was a stone carver and sculptor married to a widow, Annie. They had four children. Hannah, with her family, lived in one of the dwellings at Slater and Bank Streets, William and his family in the other.

Renamed Ottawa in 1855, Bytown became the official seat of government two years later. Consequently, there was a building boom and William carved much of the decorative stone work seen on local buildings of the day.

By 1884, Hannah and her family moved to rented lodgings. Hannah's older sons were by this point grown up and working. John William disappeared from Ottawa sometime after 1881, perhaps to Australia. He died in his mid-thirties. George Samuel worked as a printer when he was fifteen, eventually leaving for Montreal to study at night school for his Bachelor of Divinity. He was the only son to marry and have children during Hannah's life. James Austin worked as a driver at various grocers and livery stables, in Ottawa. Sometime after 1892 he left for St. Albans, New York, where he died aged twenty-four. Thomas Ellis, the youngest son, became an accountant. For the remainder of her life, Hannah was to live with Thomas and Louise, her only spinster surviving daughter. Around 1911, Thomas bought a house on First Avenue, then close to the outskirts of town. This was Hannah's final home.

It would seem that Hannah lived a somewhat withdrawn life in these later years. She was described as having had "a gentle and unostentatious Christian life": her later years "being almost wholly shut in by physical infirmity." Her connection to the Wesleyan Methodist Church was perhaps strong in spirit, but her participation with church functions was small. Perhaps these later years of hers were the "beautiful" years of her life.

Hannah est retournée avec ses enfants dans la maison de ses parents à Ottawa. Deux années plus tard, ses parents, John et Amelia, sont morts tous deux à l'intérieur d'une période de trois mois. Comprenant deux bâtiments, les biens immobiliers et hypothéqués de John furent laissés à ses fils, Samuel et William. Samuel était comptable, et il avait une femme et un petit enfant. William était tailleur de pierre et sculpteur, et il avait épousé une veuve, Annie. Ils avaient quatre enfants. Hannah vivait avec sa famille dans une des demeures des rues Slater et Bank, alors que William et sa famille occupaient l'autre.

Rebaptisée Ottawa en 1855, la ville de Bytown devint le siège officiel du gouvernment deux années plus tard. Par conséquent, la construction monta en flèche et William sculpta presque tous les détails décoratifs en pierre qui ornent les édifices locaux datant de cette époque.

En 1884, Hannah et sa famille avaient déménagé dans un logement loué. Les fils aînés d'Hannah étaient maintenant devenus des adultes et ils travaillaient. John William est disparu d'Ottawa quelque temps après 1881, peut-être pour l'Australie. Il est mort vers le milieu de la trentaine. George Samuel a travaillé comme imprimeur quand il avait quinze ans, et est par la suite allé à Montréal pour suivre des cours du soir en vue d'obtenir un baccalauréat en théologie. Il fut le seul fils à se marier et à avoir des enfants du vivant d'Hannah. James Austin a travaillé comme conducteur pour diverses épiceries et écuries de louage à Ottawa. Peu après l'année 1892, il partit pour Saint Albans dans l'Etat de New York, où il mourut à l'âge de vingt-quatre ans. Le cadet Thomas Ellis est devenu comptable. Pour le reste de ses jours, Hannah allait vivre avec Thomas et avec sa fille célibataire Louise, la seule à avoir survécu. Vers 1911, Thomas acheta une maison sur la première avenue, alors située près de la banlieue de la ville. Ce fut le dernier foyer que connut Hannah.

Il semblerait qu'Hannah ait vécu une vie plutôt retirée durant ces dernières années. On l'a dcrite comme quelqu'un avait eu «une vie chrétienne douce et discrète» : elle passa les dernières années de sa vie «presque enfermée à cause d'une infirmité physique». Son lien avec l'église méthodiste wesleyenne est peut-être demeuré fort en esprit, mais sa participation aux cérémonies religieuses fut restreinte. Ces dernières années furent peut-être pour elle les «plus belles» années de sa vie.

Exhibition History

| 2000-2001 | Lee Dickson: Hannah, (solo) Ottawa Art Gallery⁄Galerie d'art d'Ottawa |

Exhibition Catalogue

| Fortin, Sylvie. Lee Dickson, Hannah. Ottawa Art Gallery⁄Galerie d’art d’Ottawa, 2000. |

Bibliography

| Bouchard, Claude A. "Hommage personnel àdes aînés remarquables…La Galerie d’Art d’Ottawa…l’artiste Jerry Grey d’Ottawa et l’autre par l’artist Torontoise Lee Dickson." Ledroit [Ottawa-Hull] Dec 16 2000: A37. |

| Fortin, Sylvie. "Hannah." Tract. OAG. vol 7-2. Oct 1 2000 - Feb 1 2001. |

| "Lee Dickson: Hannah." Ottawa Art Gallery. Slate [Toronto] Dec 2000-Jan 2001: 33,Ad. |

Funding

The Canada Council

Acknowledgements

Archives of Ontario⁄Archives Publiques de l'Ontario, Canada Council⁄Counceil des Arts du Canada, Toronto Reference Library, National Archives⁄Archives Nationales du Canada, North York Library: the Canadianna Collection, Ontario Genealogical Society, City of Ottawa Archives⁄Archives municipales d'Ottawa, Archives of the Pembroke Historical Society & Champlain Trail Museum, United Church Archives, Karen Eyo, Judith Ann Heuff, Donald A. McKenzie, Bob & Louis Pilot and Colette Tougas.